Let’s Get Clear: Teach Kids to Annotate the Same Way Real Readers Do

We teachers have good intentions. We are helpers. We are cheerleaders. We are guides. And we are leaders. (Apparently we are good at accidental rhyming too!) But sometimes our good intentions can actually get in the way of our best teaching. We’re all guilty of it, myself included.

I was sharing this idea yesterday with a team of teachers I’ve been coaching for a couple of years. One teacher shared how she caught herself in a good intention gone bad spiral just the other day. She was teaching kids a new method for solving a math equation and she was demonstrating the steps she wanted them to take, which included drawing shapes, putting a box around them, etc. As she watched her students try out the new method it dawned on her that she had actually provided too many steps to the process, and some of the steps were just gumming up the works. After a recess break, she shared her reflection with the students and asked for their feedback about how they could simplify the process. They came up with a solution and not only did she observe her students applying the new method more successfully, they all got the problem correct on an assessment a few days later.

I was so impressed that this teacher not only recognized that her good intentions weren’t leading to the outcome she expected, but that she acknowledged that she needed to make a change to improve the situation. She didn’t get defensive or feel embarrassed. She didn’t blame the curriculum or the (yikes!) the students. And she didn’t cling to her original idea just because it was hers. She observed, reflected, and made a pivot in a new direction. And not only that, but she involved her students in the process. She modeled for them what a respectful, collaborative relationship is like. Talk about trust-building!

Her example got me thinking about other ways that we well-meaning teachers put up obstacles to learning. Then annotations came to mind. I’ve seen examples in classrooms, online, and in books, about the best ways to teach kids to annotate texts. And of course the intentions are good ones. We want kids to learn to read closely. To thinking deeply. To make meaning from important works that they read. And we want them to try out all these different ways of annotating as though it will guarantee success.

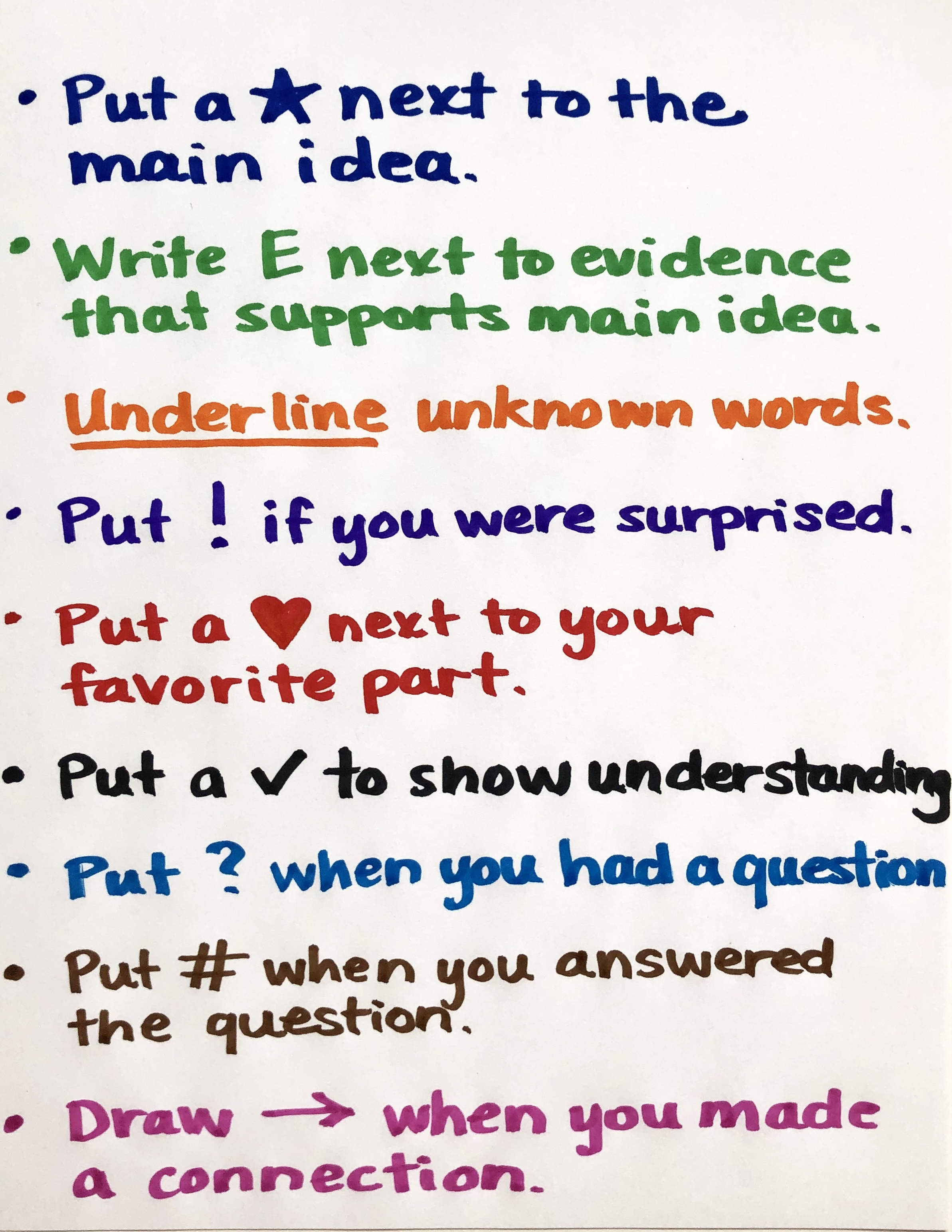

A quick online search came up with the following:

And there were more. So many more.

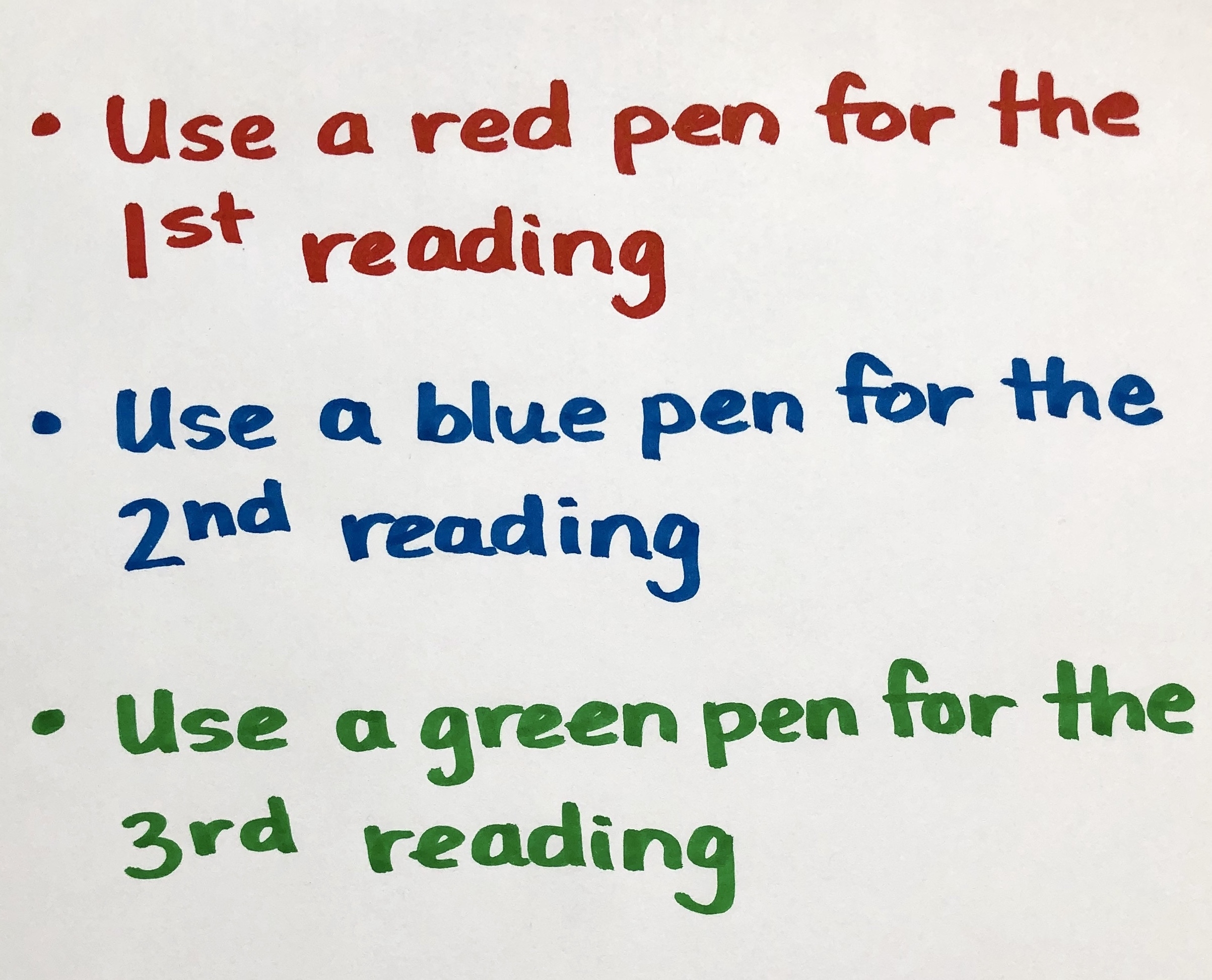

Then, we teachers might add a layer of color-coding just to keep things interesting.

Oh, honey.

I bet you’ve seen this too. And there are really good intentions here. We want kids noticing things when they read. We want them to be thinking while they read. We want them to read and reread for greater understanding. We want them to be prepared to talk about what they read. Yes, yes, yes, and yes. We do want all these things. (Let’s be honest, we want even more than that, but let’s stay focused…)

But can we pull back for a moment and take a good look at all the hoops we’re asking kids to jump through in order to accomplish our overarching goal of improving kids’ ability to read well? Why don’t we wade through the clutter and clear a more direct path for students. We can do it, and we can help kids in process.

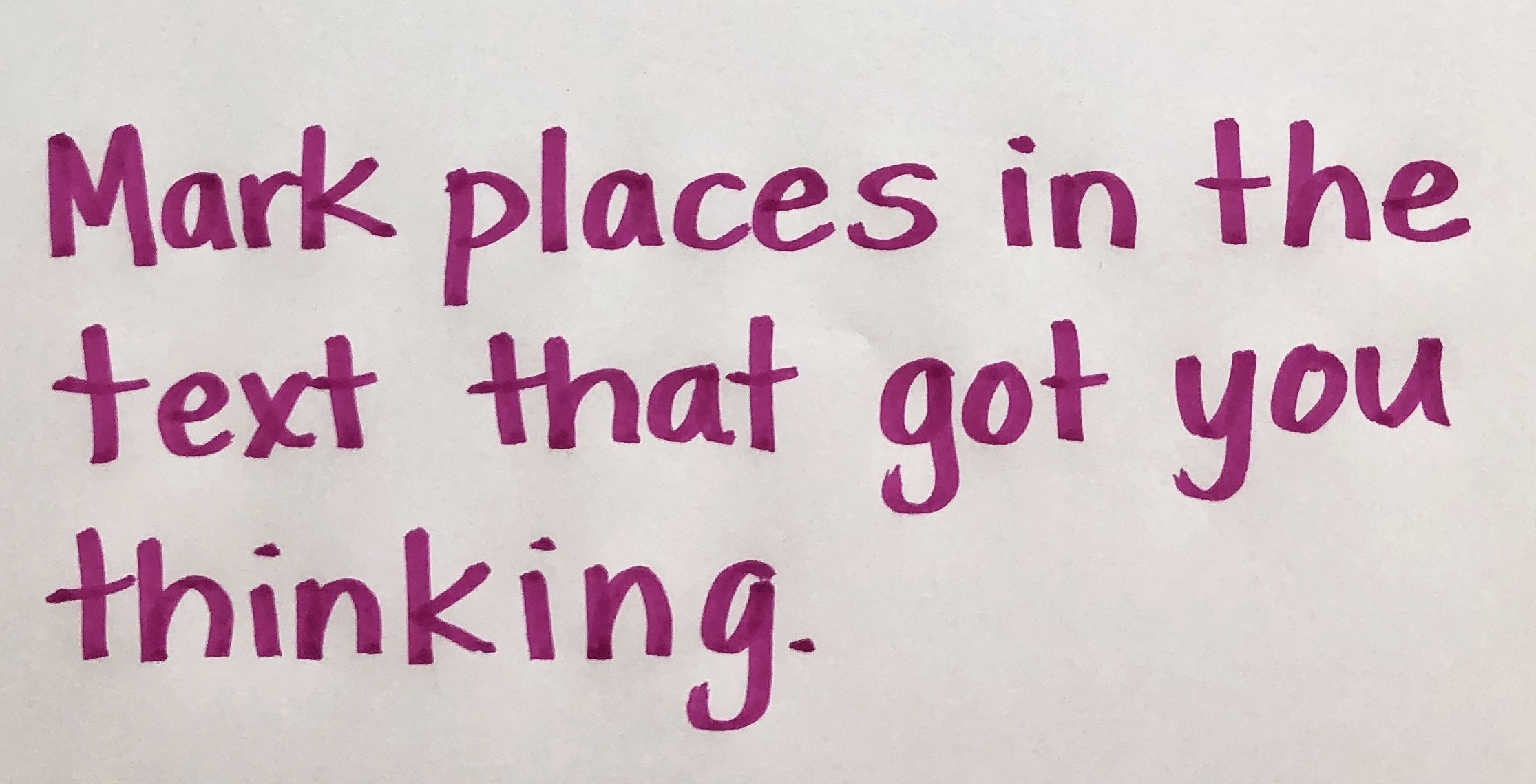

First, let’s pare down the steps and get really focused on our goal. We want kids to think about what they read. Okay, so let’s give them some simple guidelines for how to do that.

That’s it.

No really, that’s it.

Think about when you dive into a novel you’re reading, or an article for work, or a research study for grad school. Were you required to use fancy codes and colors to help you think about what you were reading? Or did you mark it up the way you saw fit, based on your intentions for reading that text? I’m betting you focused on what the text meant to you and not the types of marks you made. Am I right?

Let’s give kids the same latitude. Let’s let them decide what to focus on because it’s what’s meaningful to them. That’s what real readers do. And sometimes readers have a personal coding system they like to use. And sometimes readers use different colors that are meaningful to them. And sometimes readers make few marks at all because that’s what works for them. Notice a pattern here?

Okay, so we’ve set the expectation that they think while they read, and mark those points in the text. Now, we can focus on a specific type of thinking we want them to engage in. Here’s what I mean. A teacher could say:

“Today, we’re going to read this article about an endangered animal. You will be reading on your own and I expect you to mark places in the text that got you thinking. Today, I want you to also pay special attention to any unknown words in the article. You may want to make a special mark just for those words you don’t know yet. I often underline an unknown word like this. When we come together for our discussion I want to hear about your thinking, and we will also discuss the unknown words you found and try different strategies for figuring them out.”

Do you see how the focus is now on thinking about reading and not on a reading scavenger hunt where the goal becomes to fill your paper with codes, and emojis, and sticky notes, and rainbows, and…well you get the idea. Strip those things away and get right to the point. Mark the places in the text that got you thinking. Period. Then, depending on your learning goal and the text itself, add an additional focus that has a real purpose. Your students will find the process easier, their thinking can become clearer, and they’re likely to be ready to engage in a discussion. You’ve made the expectations crystal clear and you set them up for success.

Repeat this straightforward process with other close reading sessions that you do and help kids look for specifics that will aid them in your class discussion. Model, and model, and model the process. And for goodness sakes, find the best darn texts you can so that kids will do all the hard work to read them!